Modern maritime piracy is both similar and very different to the land based K&R model. When pirates hijack a ship, they are abducting a lot of people, but they are also taking control of the vessel and cargo as well. That doesn’t happen on land. So what was the Somali piracy business model?

When the pirates make a demand, it’s partly the kidnap for ransom model and it’s partly extortion. The ransom bit is obvious. The extortion piece may come from threatening a major oil spill or trying to negotiate the release of previously captured pirates as part of their demands.

There are a couple of key piracy hotspots around the world, the Gulf of Guinea in West Africa, and the Singapore Strait’s in the far East. The most infamous though is of course off the coast of Somalia.

There are a lot of books on the causes of maritime piracy. Whilst some try to make Somali piracy seem like a noble cause for a disadvantaged population, I don’t quite agree. Whilst international fishing in Somali waters might have been a catalyst, even that is debatable. Whatever the root cause, it evolved into a greed driven mass of criminality, and a power struggle amongst warlords.

Somali Piracy Business Model

Let’s describe a hypothetical situation which helps talk that through.

A Somali clan chief, or warlord, ruling his remote part of Somalia. He sees some of his neighbouring warlords becoming successful and earning money from maritime piracy. That means the neighbour is buying more weapons, employing more men and is upsetting the local equilibrium of power. Central government and the rule of law mean nothing in that part of the world. (That is still pretty true to this day.)

The chief knows that he must protect his clan and so decides to have a go. Given the poverty in the area, and the natural skill in his fishing fleets, he has plenty of volunteers. What he doesn’t have is money. So, he borrows it, effectively selling shares of future profit. Interestingly, during the peak of piracy, through the hawala system, you could invest in piracy from outside the country. Kenya, Dubai, London. It was all possible.

Seed Capital

Let’s say the chief now has a hundred thousand dollars in seed capital. He sends someone to go and buy the equipment he needs. Then he buys, three speed boats, or skiffs as they are called, three brand new engines, satellite phones, some weapons, ammunition, ladders and grappling hooks. He then sends those three boats, each with perhaps four or five crew out to sea for a month, to go ‘fishing.’

Was it successful?

One vessel hit’s bad weather, and sinks killing those on board. One vessel stays out until it is nearly out of fuel and has to return home empty handed. But the third one is successful and brings back a container ship. Incidentally when the pirates all got onboard, they had to leave their skiff behind and it sank.

The container ship is brought back and the men who captured it at sea now lead the group of thirty or forty men who will guard it as it is parked offshore outside the village.

The chief, speaking no English, employs an interpreter, who starts to negotiate with the shipping company that owns the ship. The negotiation goes on for three months.

Cash flow

During that time, the chief has run out of his original money, but still needs to feed the guards, and keep the crew alive. He makes a deal with local food suppliers, and khat suppliers. Khat is a chewable leaf with narcotic properties. The traders charge him triple the price for the credit but are happy to wait until a ransom is paid.

Eventually, the money is delivered, the crew and ship are released, and the guards are all paid off. The pirates that actually seized the ship are paid handsomely. Then the chief pays blood money to those that were killed on the lost skiff. Finally he pays a share of the final proceeds to those who lent him the money in the first place, and keeps the rest.

What was the Somali Piracy Business Model – Was it profitable?

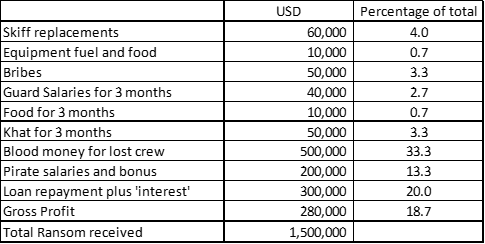

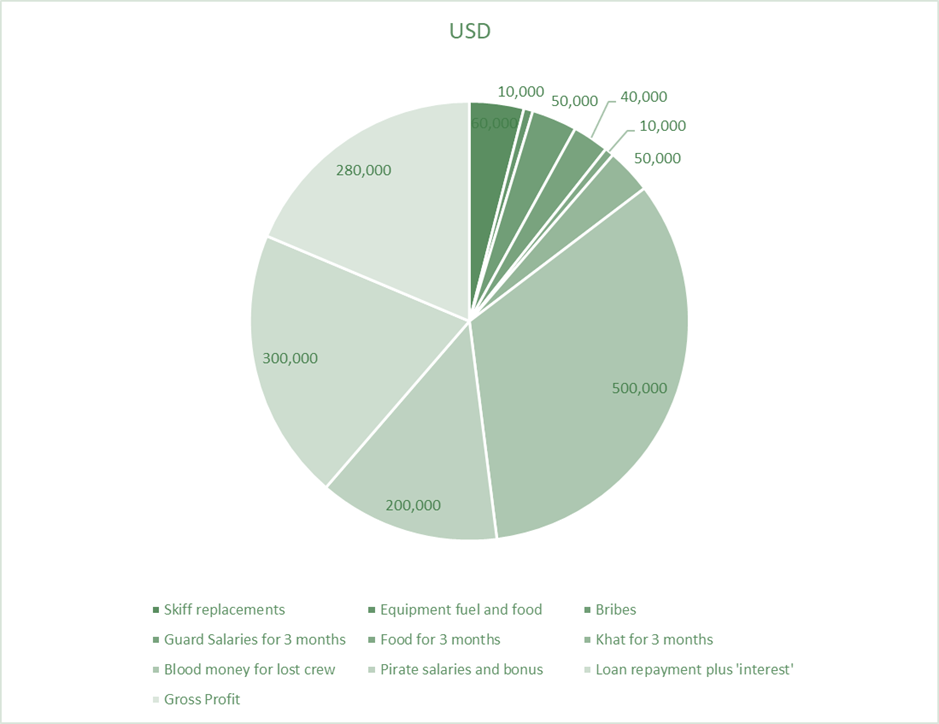

If we were to add some very rough numbers to the description above you will see what the Somali piracy business model was in more detail. In Figure 1 we can see that there is not a lot of money left over after all the costs. In fact, the pirate leader makes less than a 20% pre-tax profit margin on the business. Oh, who am I kidding, anyone else here think they paid any tax?

I am keeping the math simple, but there are a couple of comments on the table in Figure 1.

- Each of the guards on the vessel would get paid about ten dollars a day so a thousand dollars per man over three months.

- For every day they were guarding, it probably cost another twenty dollars per man per day in narcotics and food. A classic case of keeping the men happy.

- From the ransom payment, the pirate kingpin needs to pay a considerable amount of profit share to the people who provided the seed capital in the first place.

- The largest expense of all is the blood money paid to the families for the men that died. In this case, it’s a third of the total ransom received.

Ransoms and profit slowly increased

In the early days, a ransom of between a million and a million and a half was normal, that meant that the pirate kingpin made up to half a million depending on a range of factors. If he made that on his first project, then he was able to sustain a healthy business model into the future. If his first project failed miserably, then he was massively in debt and probably worried about his personal health and that of his clan.

As time passed, the ransoms increased until they averaged three or four million dollars per vessel. That increase went straight to the bottom line and helped the clan chief evolve his fiefdom. He could employ more men, buy more weapons, and yes he could also put some more money into the local economy. Though that was probably only enough to influence his clan that the terrible trade was worthwhile. In the meantime, and yes it is cynical, people were paid to promote the original story of defending their fishing rights.

I think we can see that capturing foreign crews off cargo vessels is a far cry from that.

Case Study

The MV Faina was captured by Somali Pirates in 2009. Her cargo was an arms shipment bound for Kenya. Onboard were vast quantities of weapons including RPG’s and thirty three tanks. The privates originally demanded 35 million USD in ransom, a considerable sum. The final settlement figure was just over three million USD. During the whole period several warships stood off at a distance from the MV Faina. They had to ensure that none of those weapons were transferred onshore. Simply put it wouldn’t have been allowed to happen because that level of firepower in the hands of a Somali warlord. It would have broken the balance of power for the whole country and put the fragile new western supported government at risk.

This article is an excerpt from How To Deliver a Ransom by Rob Phayre.

Available to order now for February 2025 delivery

True Crime, Non-Fiction – To Be Released in February 2025

You can find links to all your favourite book stores here: www.HowToDeliverARansom.com

Published by Rob Phayre Ltd http://www.robphayre.com

So now you know ‘What was the Somali Piracy Business Model’

Rob Phayre is the author of The Ransom Drop, a novel about maritime kidnapping and ransom delivery. It may be found on Amazon here.

Rob is also the author of How To Deliver A Ransom. It’s a non-fiction true crime study of the kidnap for ransom industry. That’s available here.

I hope you enjoyed this article on ‘How did Somali pirates get paid.’ There are more resources available in the blog and on the main web page. Its all available here.

And finally, if you would like to connect with Rob on the topic of kidnap for ransom. Please ask any questions please approach through social media, he would love to here from you. Links are here.